Who were the inmates?

![]()

The decision to establish a prison camp on Goli Otok was made in early 1949 and the first inmates began to arrive there already in July that year. In the past, the islands had often been used for isolating individuals and groups who were considered, for various reasons, a political or social threat. During the First World War, Goli Otok itself served as a prison camp where the Austro-Hungarian army kept its prisoners of war. Following the end of the war, the island was abandoned and remained deserted up until 1949. Desolate, isolated, and far from Yugoslavia’s eastern borders, wherefrom the hypothetical attack was expected to come, Goli Otok was chosen by the Yugoslav authorities as an ideal place for interning its pro-Soviet minded citizens.

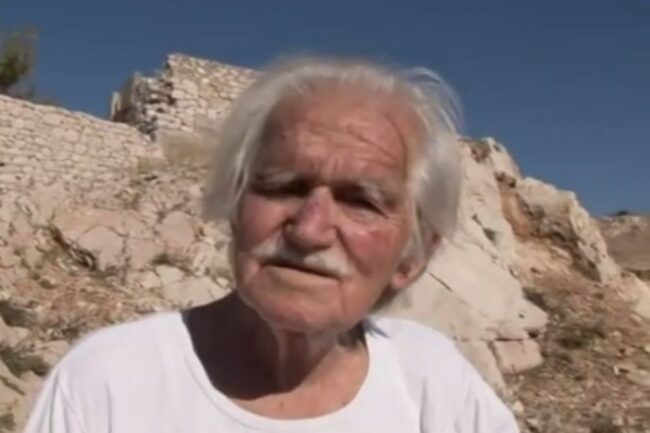

Alfred Pal, a former prisoner in Goli Otok

![]()

Although all those who were imprisoned at the camp in Goli Otok were treated as supporters of the Cominform Resolution (Rezolucija Informbiroa, IB) and therefore referred to as ibeovci, the facts suggest that they were not a politically or ideologically homogeneous group. On the one hand, there is no doubt that they did include those who considered the USSR’s criticisms of Yugoslavia justified, believed Stalin more than they believed Tito, and were willing, under certain conditions, to support a coup d’état and change of government in the country. However, the fact is that the prison camp in Goli Otok would come to host various individuals who had nothing to do whatsoever with support for the Soviet Union or, in particular, with any activities against the state. The entire situation was exploited for staging a crackdown on all dissenters and critics of the regime. Some individuals were denounced and interned out of rather low-minded motives, which boiled down to personal enmities, conflicts, and other forms of strained interpersonal relations.

The Number and Structure of the Inmate Population

![]()

The exact number of ibeovci imprisoned in Goli Otok is unknown. The latest research suggests that the number is around 13,000 people. They included people of various ages, high-ranking politicians, professional soldiers and policemen, professors and students, peasants, unskilled workers and managers. Although there were inmates from every constituent republic of Yugoslavia, in terms of ethno-national affiliation most of them were Serbs (44%), Montenegrins (21%), and Croats (16%). The disproportionately high number of prisoners from Montenegro was interpreted by reference to their longstanding ties with Russia, as well as the poor treatment of Montenegro and its cadres in the Yugoslav federation after the war.

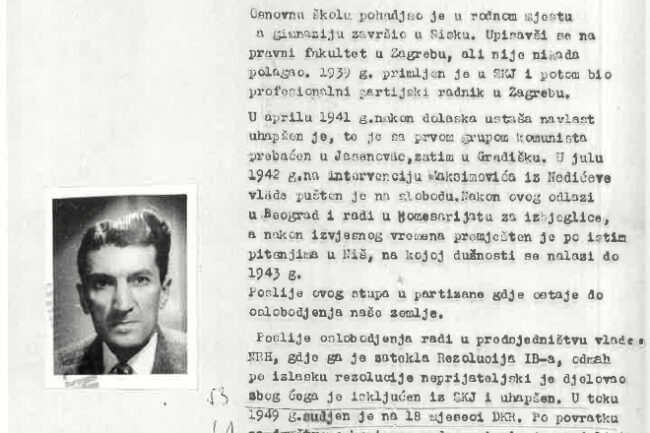

The file of Milovan Zec, imprisoned in Goli Otok

![]()

Most of the inmates were men, but the prison camp system processed almost 900 women as well. Due to torture, exhaustion, and disease, Goli Otok claimed the lives of 287 people.

Arriving in Goli Otok

![]()

Identifying potential dissenters, in concrete terms, pro-USSR minded citizens, was entrusted to the UDB (Uprava državne bezbednosti – State Security Administration), Yugoslavia’s secret police. Upon arrest, suspects underwent a rather brutal interrogation process, which a number of them did not survive; then came the conviction. Most suspects were convicted by administrative courts and the most common punishment was so-called community service. A minority of defendants were tried in a court of law, albeit in political show trials, without adequate legal representation, with the verdict most of the time known in advance. Active military personnel were convicted by military courts. Shortly upon sentencing, convicts would be transferred to prison. For most of those sentenced to community service, the final destination was Goli Otok.

The Yugoslav ship Punat, used for ferrying prisoners to Goli Otok

![]()

Convicts were brought by train to the port of Bakar and then transported by ship to Goli Otok. The entire process took place in secret, just as the existence of the camp itself was a secret for the rest of the Yugoslav public. Over time, the organisation of the prison system in Goli Otok underwent certain transformations; therefore, one may speak of four different camps: Stara Žica (1949–1950), Velika Žica (1950–1954), Work Site No. 5 for women (1951–1952), and Petrova Rupa (‘Petar’s Hole’, 1950–1954). In addition, another two camps were established on the nearby island of Sveti Grgur, one for women and one for officers of the Yugoslav People’s Army.

Serving Time in Goli Otok

![]()

The main purpose of the camp in Goli Otok was political re-education. This was meant to be achieved by humiliating the inmates, by various forms of psychological and physical abuse, and, in particular, by hard forced labour in the island’s stone quarry and mine. In addition, the inmates themselves were also forced to ‘investigate’ and denounce each other to the management of the camp, as well as to take part in mutual physical abuse. Since they were imprisoned for the same reasons, the living and working conditions of the women held in Goli Otok and Sveti Grgur were similar to those of their male counterparts. Over time, small-scale industrial facilities were developed in Goli Otok, where inmates were employed in making furniture, floor and wall tiles, as well as small ship repairs. The revenue went to the camp management, that is, to the UDB. These activities, especially those related to stone quarrying, served as an excuse for officially renaming the camp Radilište Mermer (‘Marble Labour Camp’).

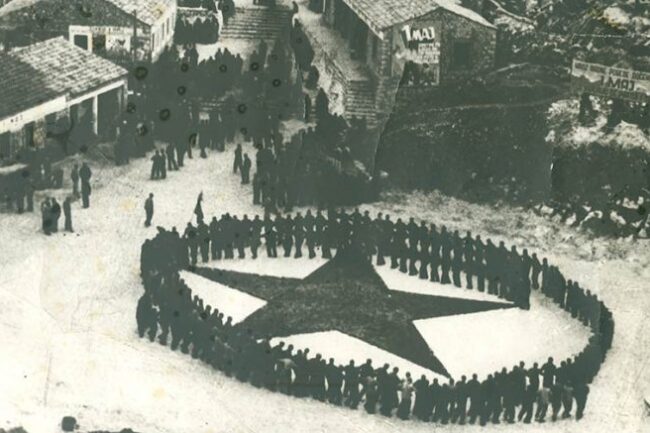

Prisoners lining up in Goli Otok

‘Petar’s Hole’

![]()

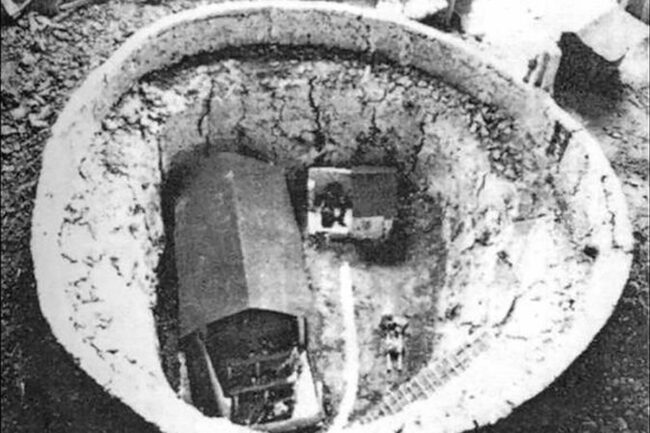

The worst living and working conditions were experienced by those who were assigned to Radilište 101 (R-101 – ‘Work Site 101’), better known as Petrova Rupa (‘Petar’s Hole’). It housed ibeovci who were considered a particular threat because prior to the rift with the USSR they occupied high military and political posts in Yugoslavia. This camp within a camp was located in an abandoned mine pit, in which wooden barracks were erected to house prisoners. Petrova Rupa was separated from the rest of the camp on Goli Otok by barbed wire and a wall. Imprisonment in Petrova Rupa came down to performing pointless tasks, such as carrying rocks around or breaking them into smaller pieces, various forms of humiliation and subjection to harsh forms of physical violence. These enhanced ‘re-education’ methods were meant to force prominent Yugoslav communists to confess their errors regarding their relations with the USSR and Stalin, whereupon their confessions would be publicised in the media. Unlike those who decided to repent, there were also those who chose to take their own lives as a result of relentless torture.

‘Petar’s Hole’

Women’s Camp(s)

![]()

Most of the women imprisoned in Goli Otok were not communists, former Partisans, or socio-political workers who approved of the Cominform Resolution, but the wives, mothers, sisters, or other relatives of convicted ibeovci. The women’s camps were located in Goli Otok and the neighbouring island of Sveti Grgur. The circumstances of their arrival and time spent at the camp were quite similar to those of their male counterparts. Immediately upon arrival, they would be greeted by a špalir, that is, a double row of ‘senior’ prisoners between whom they were forced to walk (i.e. run the gauntlet), receiving blows from every direction. The rest of the sentence comprised physical torture and punishments, as well as severe forms of forced labour. For the duration of their stay, female inmates were prevented from contacting the outside world, including their family members.

Eva Nahir Panić, imprisoned in Goli Otok because she refused to renounce her husband Rade Panić, falsely accused of spying for the USSR

Let's connect

Connect with us on social networks