Yugoslavia – ‘Soviet Satellite No. 1’

![]()

Leading the victorious army in the Second World War, at the end of the war the Yugoslav communists also seized power in the newly created Yugoslav socialist federation. During the next few years, their main model in organising Yugoslavia’s political, economic, and social life would be that of the Soviet Union. Although the communists would eventually take power in the remaining countries of Eastern Europe as well, it was Yugoslavia that acquired the nickname of ‘Soviet Satellite No. 1’, due to its rigour in copying the Soviet model.

Images of Stalin and Tito on Yugoslav streets before the Cominform resolution

![]()

This state of affairs did not continue for long. While the war was still on, it was already clear that the Yugoslav antifascist resistance movement, the largest and best organised in Europe, would secure for the Yugoslav communists a position in society different from that occupied by their counterparts in the countries liberated by the Red Army. A unique position would come to be occupied by Josip Broz Tito as well, the leader of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia and the victorious Partisan movement. A strong cult of personality began to be constructed around Tito already during the war, which continued after the liberation.

The Cominform Resolution

Official Moscow’s disapproval of Belgrade’s appetites in foreign policy, especially regarding the issue of the need for creating the so-called Balkan Federation, as well as Stalin’s increasingly pronounced animosity toward Tito, resulted in frequent critiques of Yugoslavia’s Communist Party and state leadership. The decisive moment that would shape the future Yugoslav-Soviet relations was a resolution of the Cominform, the body that the Communist Party of the USSR used to control all the communist parties of Europe, adopted in June 1948.

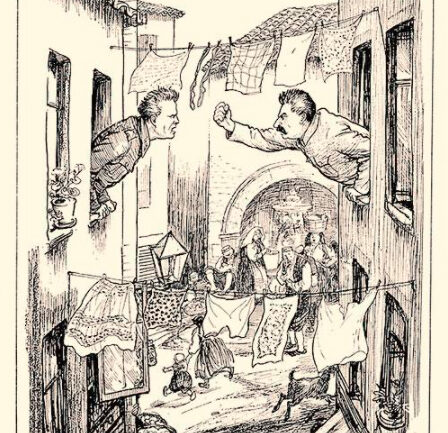

The rift between Stalin and Tito in Western media

In the Resolution, Yugoslavia was accused of betraying basic communist principles as well as committing numerous errors in its internal and foreign policy. To everyone’s surprise, Tito and Yugoslavia did not accept the criticism, but instead denounced this attack by the members of the Cominform as inaccurate and unfair. Despite the fact that the Yugoslav economy at the time depended for the most part precisely on cooperation and exchange with the USSR and other communist states and that its relations with the West were quite poor in every respect, the Yugoslav leadership with Tito at the helm chose to resist.

„Ibeovci“

In addition to the consequences brought on by the severance of diplomatic, economic, cultural, sport, and other relations, the newly emerging situation also constituted a threat to the sovereignty and integrity of Yugoslavia. The accumulation of armed forces and frequent skirmishes on Yugoslavia’s borders were viewed by many as a step toward a military aggression against the country. With that in mind, those Yugoslav communists who continued to believe in the infallibility of the Soviet Union and Stalin were regarded as a significant source of instability. Such individuals could be found on all levels of politics and government, from the lowest-ranking local officials to some of the main decision-makers in the federal government and those of individual constituent republics. A particular problem concerned communists in the echelons of the Yugoslav Army (Jugoslovenska armija, JA), especially those who occupied high commanding positions. That these fears were not entirely unjustified, in other words, that this was not just a bout of irrational paranoia and a tendentious conspiracy theory is suggested by the fact that during the summer of 1948 several high-ranking army officers were involved in a plot to stage a coup d’état. The so-called Generals’ Plot involved the then chief of the general staff of the Yugoslav Army, Arso Jovanović; assistant director of the Main Political Bureau of the Yugoslav Army, general Branko Petričević; and head of the Yugoslav Army’s Agitation and Propaganda Bureau, colonel Vlado Dapčević. When their activities against the state were thwarted, the three officers tried to defect to Romania. In that attempt, Jovanović was killed at the border, whereas Dapčević and Petričević were arrested and sentenced to long prison terms.

Vlado Dapčević, a Partisan commander and officer of the Yugoslav Army

A later police reports reads: ‘The Cominform Resolution was endorsed by 9 former participants in the October Revolution, 25 veterans from the Spanish Civil War, 233 pre-war members of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, 8 members of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, 16 members of state Central Committees, 6 federal ministers, 23 representatives in the federal Assembly of Yugoslavia, 25 representatives in state assemblies, 6 generals, 170 senior officers of the Yugoslav Army, 266 officers of the UDB [Uprava državne bezbednosti – State Security Administration, the secret police organisation of communist Yugoslavia), 170 judges, 1,307 holders of the 1941 Partisans’ Commemorative Medal, 587 disabled war veterans, etc.’.

These developments in the country, that is, the confusion sown among the Yugoslav communists by the Resolution of the Cominform, as well as increasingly open hostility from the communist states of Eastern Europe were taken by the Yugoslav authorities as a warning and incentive to act. To deal with this potential threat coming from the ‘domestic enemy’, the government decided to incarcerate the ‘Stalinists’ (staljinisti), ‘Cominformers’ (informbiroovci), or ‘IBers’ (ibeovci) in the country’s existing prison facilities and then in a special penitentiary as well, that is, a prison camp established specifically for that purpose on the island of Goli Otok.

Let's connect

Connect with us on social networks