CONTROVERSIES

![]()

The events concerning the surrender of the army and civilians at Bleiburg, as well as their treatment after the surrender still, even today, contain a number of unknowns and provoke different and controversial interpretations. In that regard, one may speak of several thematic areas that still cause disagreements and divided opinions.

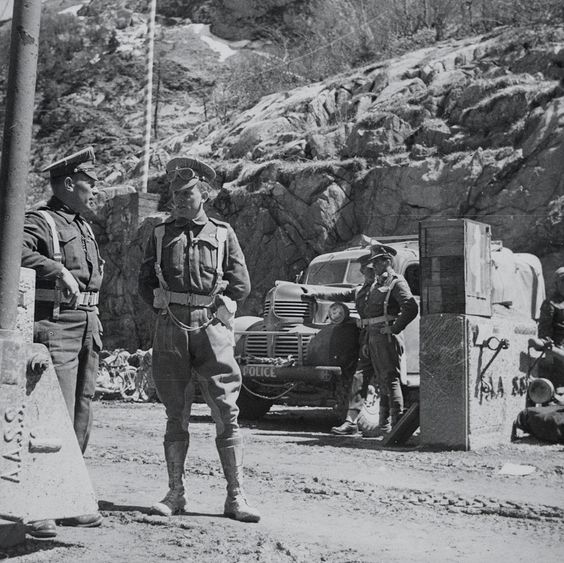

Members of the British armed forces in Austria, 1945

![]()

The first topic concerns the actions of the British army regarding the troops and civilians who surrendered to them in Austrian territory. In public discourse, and even in historiography, one can often hear the claim that the British decided to extradite these prisoners to the Yugoslav Army due to decisions made at the Yalta Conference (February 1945). The Conference did reach an agreement regarding the so-called repatriation of all citizens of the Soviet Union who had fought against the Soviet government, but there was no mention of an agreement or decision concerning the repatriation of Yugoslav citizens to the new authorities in Yugoslavia. The available sources and subsequent testimonies of those who took part in the events of May 1945 suggest that the actions of the British were conditioned primarily by their long-term political aims and current military situation on the ground. Concerned about the Yugoslav Army’s advance into Carinthia (and the Julian March or Venezia Giulia; Slovene and Croatian: Julijska krajina) and their possible capture of that part of Austria (and Italy), the British decided that accepting a large number of refugees from Yugoslavia would make it much harder for them to attain their goals. Neither was their decision affected by well-placed doubts regarding the Yugoslav army’s treatment of prisoners. With all that in mind, it becomes clear why for decades there has been so much debate about the responsibility of British politicians and military commanders for the tragic outcome that resulted following their decision to extradite prisoners who had surrendered to them over to the Yugoslavs.

![]()

The second topic concerns why the Yugoslav army treated these prisoners so brutally, soldiers and civilians alike. Reprisals against members of the defeated forces and collaborators took place all over Europe, but in terms of the sheer number of victims and the way they were killed the Yugoslav case is without compare.

Source: Public domain

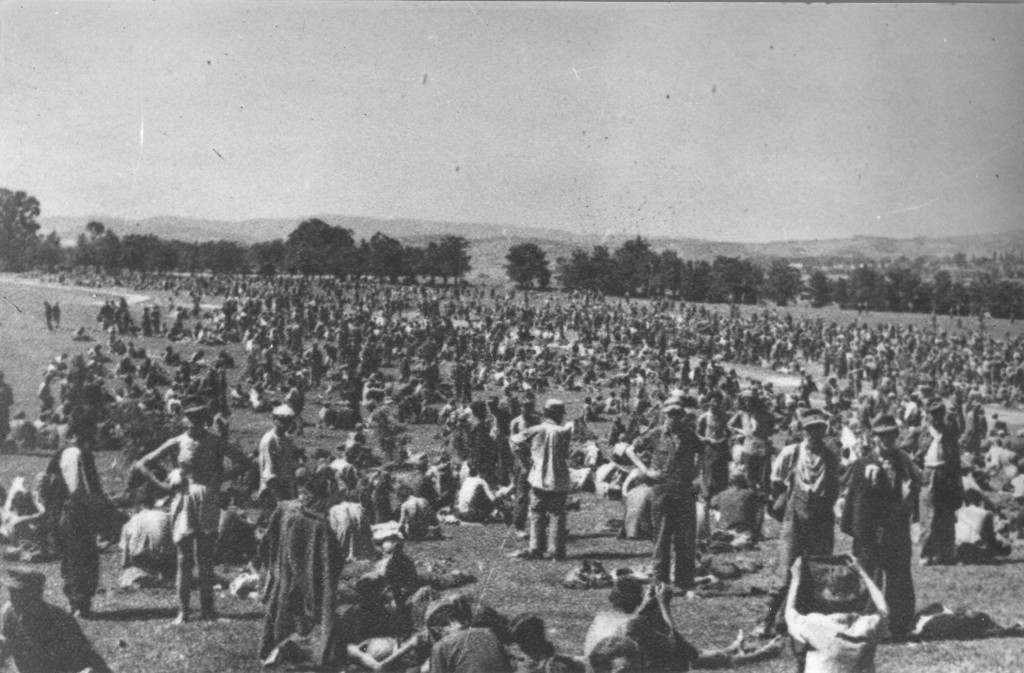

Prisoners under the watch of Yugoslav Army men

![]() According to one interpretation, this brutality was a response to the mass atrocities perpetrated during the war by members of the defeated forces, especially the Ustaše and Chetniks. However, although these atrocities were certainly committed, the actions of the Yugoslav army were entirely incompatible with the provisions of The Hague Conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners of war (1907) and the Geneva Prisoners of War Convention of 1929, which applied to Democratic Federal Yugoslavia as well.

According to one interpretation, this brutality was a response to the mass atrocities perpetrated during the war by members of the defeated forces, especially the Ustaše and Chetniks. However, although these atrocities were certainly committed, the actions of the Yugoslav army were entirely incompatible with the provisions of The Hague Conventions regarding the treatment of prisoners of war (1907) and the Geneva Prisoners of War Convention of 1929, which applied to Democratic Federal Yugoslavia as well.

![]()

Another interpretation takes into account the fact that at the end of the war, members of the defeated forces were willing to place themselves at the disposal of the Western allies in a new war against the communists. Besides, even without another war, the new regime was apprehensive about the prospect of so many of its ideological opponents and enemies returning to live in Yugoslavia.

![]()

In Croatian émigré circles one could also hear opinions that following the surrender at Bleiburg an act of genocide was perpetrated against the Croat people. However, notwithstanding the terrible death toll, the genocide thesis is untenable. The prisoners were not murdered because they were ethnic Croats, but because they were regarded as enemies and criminals. Besides, Yugoslav Army units, its commanders and regular soldiers alike, even those who took part in the executions, comprised a large number of ethnic Croats as well. The fact that most of the victims were ethnic Croats is due primarily to the fact that so many Croatian prisoners had been captured.

![]()

The third topic, involving the greatest number of unknown facts and controversies, concerns the number of those who were killed after the surrender at Bleiburg. Beginning already in May 1945, various calculations have been made regarding the number of people in the refugee columns and then the number of victims as well. The numbers vary depending on the provenance of the source, with the highest tallies cited by ethnic Croats who managed to escape or survived extradition to the Yugoslav army and then emigrated and lived abroad, while the lowest figures come from former commanders of the Yugoslav Army. One should note that in socialist Yugoslavia this entire topic was never discussed in public, no efforts were made to uncover the burial sites, and no historiographic or demographic studies were conducted on the basis of existing archival documents, statistical data, population censuses, and the like.

Source: Povijest.hr

Soldiers and civilians in the field at Bleiburg

![]()

The first scholarly studies on this topic came out in the mid 1980s, with Bogoljub Kočović and Vladimir Žerjavić as the two most prominent authors. Interest in this topic took off following the advent of democracy and breakup of Yugoslavia, when a number of research projects were initiated, seeking to establish the facts concerning Bleiburg and the various “ways of the cross”, thereby including the number of victims as well. Thus far, the most extensive and comprehensive work regarding the topic has come from the historian Martina Grahek Ravančić. Due to the lack of historical sources and the passage of time, the exact number of refugees and victims will never be precisely determined. One of the controversies that are often heard in public discourse concerns the number of those killed in the field at Bleiburg itself. The truth is that there were no mass executions in the field itself, but the confusion that accompanied the surrender did result in armed skirmishes, in which members of the Yugoslav Army killed several dozen people.

![]()

Regarding the mass executions that ensued when the prisoners were marched from Austria into Yugoslavia, the numbers cited in Croatian émigré circles run as high as 500,000 (mostly ethnic Croats), which is, according to all the available data, a grossly exaggerated number. By contrast, in their recollections, former commanders of the Yugoslav forces and participants in these specific events either ignore the topic of mass executions or seek to minimise the numbers down to a few thousand dead, murdered or killed in the final military operations of May 1945.

![]()

It is currently agreed that the most accurate assessment produced so far is that of Vladimir Žerjavić, who estimated that in May 1945 around 80,000 servicemen and some 45,000 civilians found themselves in the field at Bleiburg. To this, one should also add the 30,000 or so ethnic Croats, Slovenes, and Serbs who were interned in the British PoW camp at Viktring near Klagenfurt. According to that assessment, the executions that followed after May 15th took the lives of around 70,000 people in total, including 60,000 ethnic Croats (around 50,000 soldiers and up to 10,000 civilians), around 10,000 ethnic Slovenes, and around 2,000 Montenegrins and Serbs. Martina Grahek Ravančić accepts Žerjavić’s estimate as a valid starting point, but complements it with more recent findings in the field, bringing the total number of victims to between 80,000 and 90,000.

Follow us

Connect with us on social networks