THE ESTABLISHMENT AND STRUCTURE OF THE CAMP

![]()

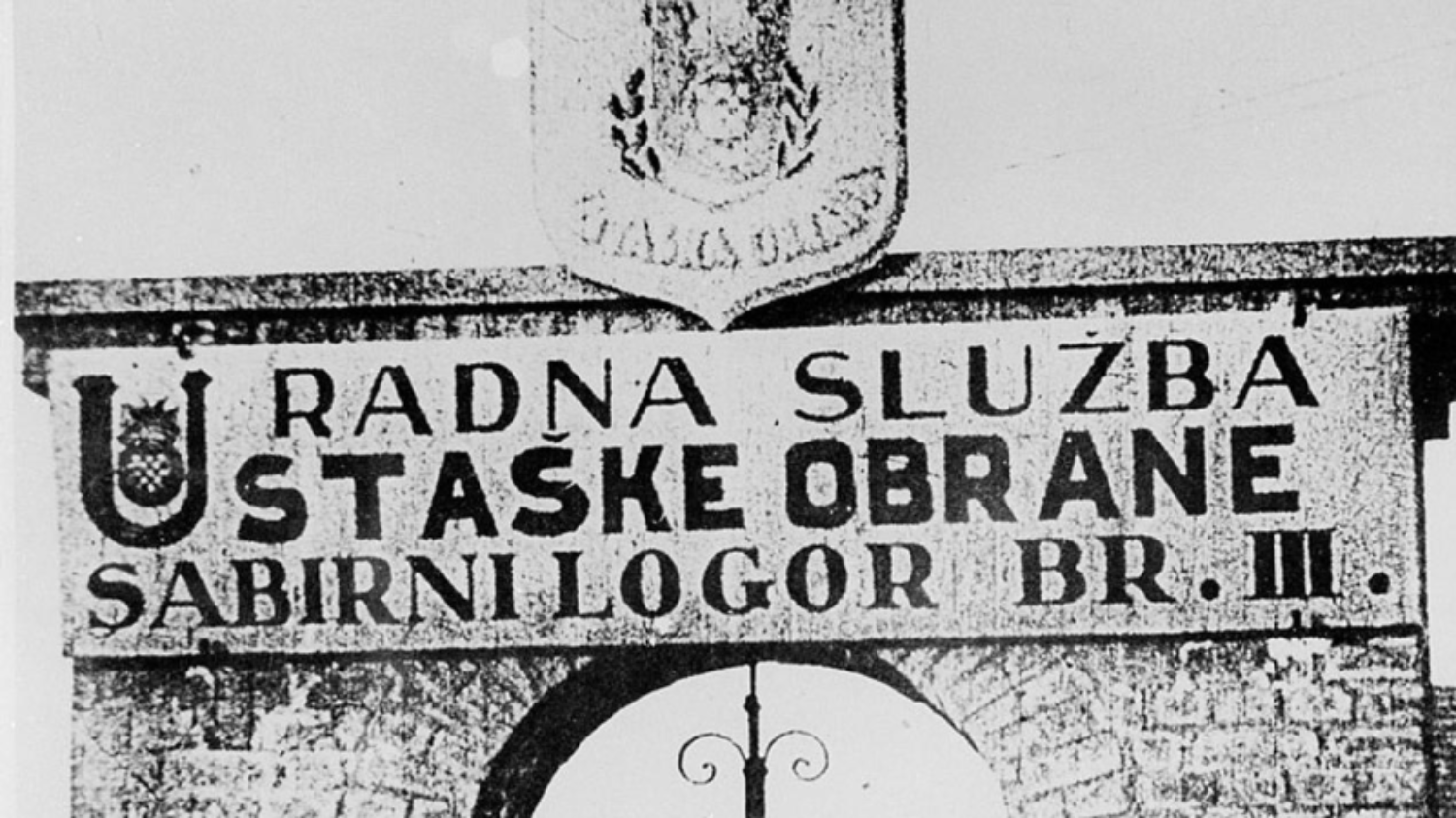

When Lika and the Croatian Littoral officially became part of the Italian occupation zone in summer 1941, the Ustaše authorities were forced to close the system of camps centred at Gospić. One of the main reasons behind the Italians’ decision to close the camps was the growing insurgency of the local ethnic Serb population and the organised Partisan resistance movement led by the communists, which was likewise gaining strength. It was decided that the new prison camp system should be located near the village of Jasenovac, close to the confluence of the rivers Una and Sava, where the first prisoners began to arrive in late August 1941. The official name of the camp was “Ustaše Defence – Command of the Jasenovac Concentration Camps” (Ustaška obrana – Zapovjedničtvo sabirnih logora Jasenovac), but in various documents it is also referred to as “Jasenovac Concentration Camp” (Koncentracioni logor Jasenovac), “Jasenovac Collective Camp” (Sabirni logor Jasenovac), and “Jasenovac Concentration and Labour Camp” (Sabirni i radni logor Jasenovac). Starting from a few barracks surrounded by barbed wire, over the next four years the camp grew into a complex comprising five segments: the sub-camps at Krapje and Bročice, the sub-camps “Ciglana” (Brickworks), “Kožara”, and Stara Gradiška. The system of camps at Jasenovac covered an area larger than 200 square kilometres (22,000 hectares or 77 square miles or 49,500 acres).

Inmates forced to work on a dike

![]()

The organisation of the prison camp system at Jasenovac was modelled after that of the Nazi concentration camp at Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg, which means that it served more than one purpose. The latter camp, located outside Berlin, held political and war prisoners, criminals, as well as people considered racially or biologically inferior. They all had to endure torture on a daily basis, including starvation, hard labour, and medical experiments, but were also subjected to mass murder as punishment. In autumn 1941 Sachsenhausen also hosted Vjekoslav Maks Luburić, who came there for training, before returning to the NDH, where he was given an opportunity to implement his newly acquired skills as commander not only of Jasenovac, but of all Ustaše-run camps. The prisoners of Jasenovac were forced to work in construction and agriculture, various kinds of workshops, the camp’s brickworks, sawmill, bakery, etc. The conditions of work at the camp were extremely harsh, while the behaviour of the Ustaše guards was particularly brutal, which included subjecting inmates to sadistic violence and summary executions on the spot. In addition to these individual murders, throughout the camp’s time in operation the Ustaše also subjected inmates to mass killings.

THE INMATES

![]()

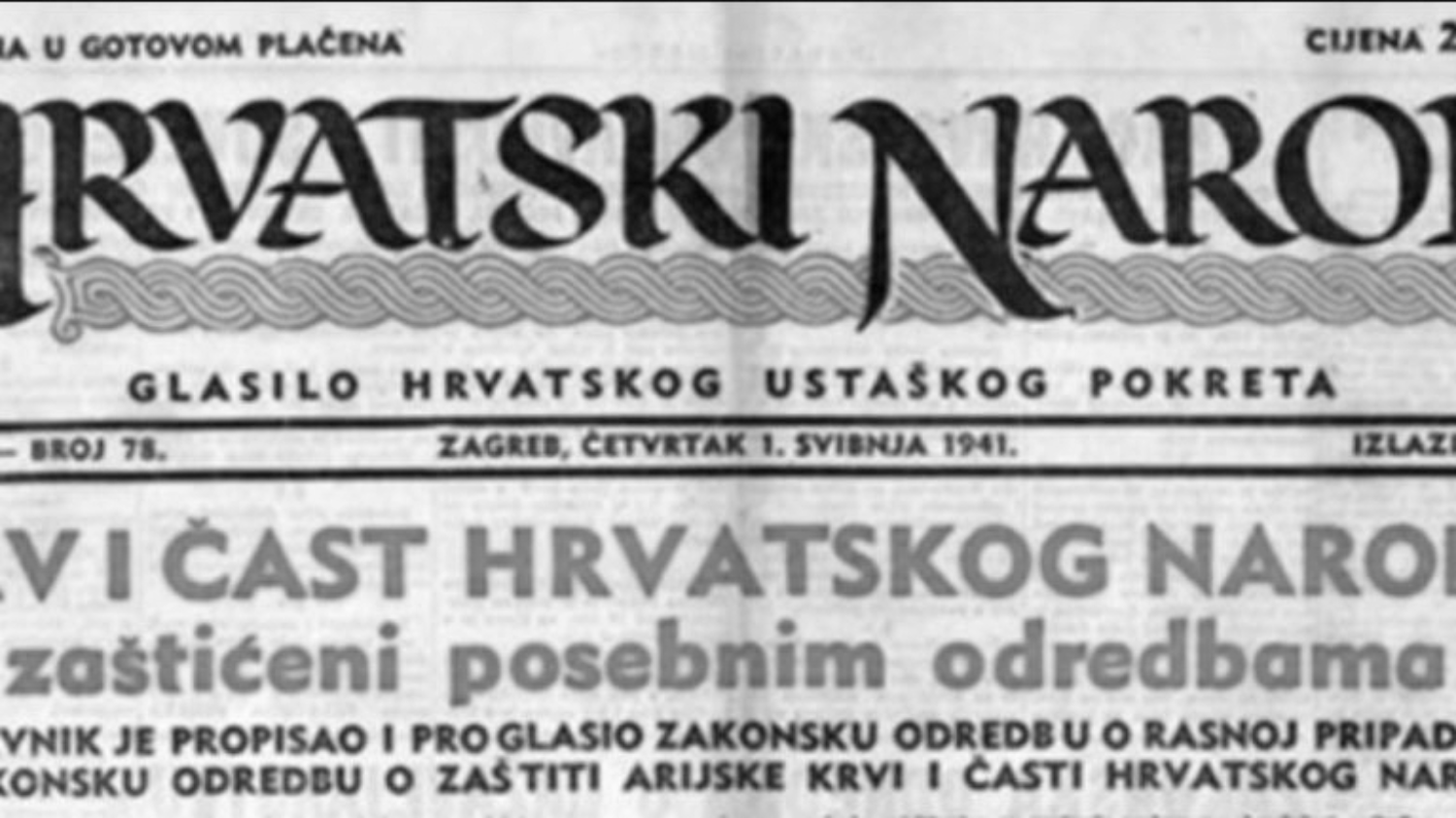

For the most part, the inmates comprised ethnic Serbs, Roma people, and Jews, whose only “fault” was their ethnic, religious, or racial affiliation. Their deportation to the camps was legalised through a series of official decrees made by the Ustaše regime, intended to protect Croatian society from those who were declared enemies of the state. Among those decrees, one should highlight the “Legal Decree concerning the Defence of the People and the State” (Zakonska odredba za obranu naroda i države, 17 April 1941), “Legal Decree on Racial Affiliation” (Zakonska odredba o rasnoj pripadnosti) and “Legal Decree on the Protection of the Aryan Blood and Honour of the Croat People” (Zakonska odredba o zaštiti arijske krvi i časti Hrvatskog naroda, 30 April 1941), the “Special Legal Decree and Order” by the Poglavnik (“Leader”), Ante Pavelić, of 26 June 1941, which stated that whoever was caught spreading rumours about the “alleged” persecutions would face the summary court, and the “Legal Decree on the Forced Interment of Undesirable and Dangerous Persons in Concentration and Labour Camps” (25 November 1941), etc.

Robbing prisoners of their belongings on arrival in the camp

![]()

Ethnic Croats as well as members of other ethnicities were also brought to the Jasenovac camp, but mainly as political prisoners. The most numerous among them were communists and anti-fascists, dissenting intellectuals, priests, etc.

The first inmates, who arrived in Jasenovac in the summer of 1941, were mostly men, Jewish and Serb. Over time, more and more women were also brought to the camp. They included communists and members of the Partisan movement, but for the most part Serb and Jewish women. Most of the women were held at the Stara Gradiška camp, a former penitentiary some 40 kilometres (25 miles) from Jasenovac. Along with women, the camp began to accept children as well.

![]()

Separated from their mothers, who were either murdered or sent to forced labour in Germany, some of these children were saved from death through adoption by Croat families, but a significant number of them remained in the camp and fell victim to individual and mass killings.

THE COMMANDERS

![]()

The establishment of the Jasenovac Concentration Camp was a state project of the Ustaše regime, which means that the responsibility for the crimes committed there applies to every official of the NDH, from the highest to the lowest ranks. This primarily applies to Ante Pavelić, the “leader” (Poglavnik) of the NDH; Eugen Dido Kvaternik, director of RAVSIGUR (Ravnateljstvo za javni red i sigurnost – Directorate of Public Order and Safety), i.e. the central police body of the NDH, who was also commander of UNS (Ustaška nadzorna služba – Ustaša Supervisory Service); Andrija Artuković, minister of the interior; Slavko Kvaternik, minister of the armed forces and Pavelić’s deputy, and many other high-ranking political and military officials.

Maks Luburić

![]()

Concerning the direct management of the Concentration Camp and direct responsibility for the living conditions and mass murders of inmates, several names should be singled out. Vjekoslav Maks Luburić, as head of UNS Section III, was also in charge of all Ustaše-operated camps in the NDH. He often spent time at Jasenovac, supervised the activities, and murdered prisoners by himself. He exhibited his cruelty in numerous instances away from the Jasenovac camp as well, taking part in the persecution and killing of Serbs, partisans, and communists. Ivica Matković was a close associate and confidant of Maks Luburić, and, for a while, the commandant of the camp. He committed a number of mass and individual murders, not only inside the camp itself, but also in the surrounding Serb-populated villages. Ljubo Miloš commanded the forced labour unit at Jasenovac III – Ciglana (the brickworks), before being made deputy commander of the entire camp. For a while, he also served as commandant of the Ustaše camp at Lepoglava. He personally murdered prisoners and led “cleaning” operations in Serb-populated villages, and took part in mass atrocities against the Serb population. One of the most brutal commandants of the camp in Jasenovac was a priest, Miroslav Filipović Majstorović. Due to his involvement in mass murders of Serbs around Banja Luka, he was dismissed from the Franciscan order, whereupon he joined, at Maks Luburić’s suggestion, the Ustaša Defence, which supervised the operation of all Ustaše-run camps. He commanded Jasenovac III – Ciglana, and then the sub-camp at Stara Gradiška. He personally participated in mass and individual executions of prisoners. Likewise noted for his brutality was Ante Vrban as well, who had participated in mass atrocities against ethnic Serbs in Lika and Jews at Jadovno even before coming to Jasenovac. At the Jasenovac camp he murdered prisoners by himself and was remembered by organising mass executions of children. The camp was also commanded by Dinko Šakić.

Ljubo Miloš

![]()

Apart from commanding and taking part in the killings, Šakić was one of the organisers behind the destruction of evidence pertaining to the crimes (digging out and incinerating the corpses) during spring 1945. Dominik Hinko Piccili was in charge of forced labour, notorious for his brutal treatment of slave labourers. He designed the makeshift crematorium (Pićilijeva peć, “Piccili’s oven”) where prisoners were burnt dead and alive. The crematorium was also used for the destruction of evidence in spring 1945.

THE DISMANTLING OF THE CAMP

![]()

By spring 1945 it was evident that the Third Reich and its allies were losing the war. Given the Yugoslav Army’s successes in the field, as well as the increasingly intense air raids conducted by the Allies’ air forces against targets around Jasenovac, which were strategically important for the German army’s retreat from the Balkans, the Ustaše authorities decided to abandon the concentration camp. On the orders of Maks Luburić, the camp was meant to be completely destroyed and the remaining prisoners eliminated. The last mass execution took place on 21 April 1945, when the Ustaše murdered around 700 women from Stara Gradiška, as well as dozens of men. On the following day, the same fate was meant to befall the remaining prisoners as well.

Jasenovac in April 1945

![]()

To avoid such a scenario, a group of prisoners led by the communist Anto Bakotić decided to attempt to break out from the camp. In the early hours of April 22nd, 600 of the remaining inmates attacked the guards, broke through the gate, and made a run for freedom. Only around a hundred of them would succeed. The remaining several hundred prisoners who did not dare to partake in the breach were murdered by the Ustaše over the next few days. Ustaše units left Stara Gradiška on April 24th and Jasenovac on 1 May 1945, leaving in their wake ruins in the camp and the vicinity. On the same day, Yugoslav Army units entered the abandoned prison camp complex without a fight.

Follow us

Connect with us on social networks